© DVN, een project van Huygens ING en OGC (UU). Bronvermelding: Vibeke Roeper, en, in: Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. URL: https://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/vrouwenlexicon/lemmata/en [13/01/2014]

JANS, Lucretia, also known as Lucretia van der Mijlen (born Amsterdam, c. 1602 – died after 1641), merchant’s wife, suspected of complicity in the mutiny on the Batavia and the subsequent massacre of many of the shipwrecked survivors. Daughter of Jan (or Hans) Meynertsz, cloth merchant, and Steffanie Joosten. Lucretia Jans married (1) Boudewijn van der Mijlen (c. 1599-1629), diamond cutter, on 18 October 1620 in Amsterdam; (2) Jacob Cornelisz Cuick, sergeant, on 12 October 1630 in Batavia. After the death of her second husband, she possibly married a certain Johannes Hilkes. It is not known if Lucretia had children with any of these husbands.

In October 1628 Lucretia Jans left for the East Indies on the Batavia, a ship belonging to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). She was going to join her husband, who had travelled to the Indies earlier and had meanwhile become a trader for the VOC. Lucretia was one of the twenty women on board, and as a merchant’s wife the highest in rank. She was accompanied by her maidservant, Zwaantje Hendriks. The voyage would end in a drama in which Lucretia Jans was to play an important part. Thanks to eye-witness reports and a number of letters, the events are reasonably well documented, though the exact circumstances of the mutiny remain a matter for conjecture.

In October 1628 Lucretia Jans left for the East Indies on the Batavia, a ship belonging to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). She was going to join her husband, who had travelled to the Indies earlier and had meanwhile become a trader for the VOC. Lucretia was one of the twenty women on board, and as a merchant’s wife the highest in rank. She was accompanied by her maidservant, Zwaantje Hendriks. The voyage would end in a drama in which Lucretia Jans was to play an important part. Thanks to eye-witness reports and a number of letters, the events are reasonably well documented, though the exact circumstances of the mutiny remain a matter for conjecture.

Mutiny and shipwreck

Unlike the wives of soldiers and artisans, Lucretia associated on board ship with the officers, not the crew. She was on good terms with the senior merchant Fransisco Pelsaert, the highest-ranking man on board and probably a good friend of Lucretia’s husband. Her relations with Captain Adriaan Jacobsz were strained, however. At first he had his eye on Lucretia, but she rebuffed his advances, so he turned to her maidservant, Zwaantje, who was evidently flattered by his attention. The junior merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz, an apothecary from Haarlem, fanned the flames even more, thus dividing the ship into various camps: Pelsaert and Lucretia on the one hand, and Adriaen Jacobsz and Zwaantje Hendriks on the other, with Jeronimus Cornelisz scheming in the background.

Jeronimus Cornelisz’s ambitions determined the course of events. Knowing that there were men on board who could be persuaded to mutiny, he hatched a plan to take over the Batavia, reduce the crew to a handful of faithful followers, and sail the ship as a pirate. In the meantime, Captain Adriaan Jacobsz and Zwaantje Hendriks were thinking up ways to deal with the haughty Lucretia, who was seized one evening and ‘blackened’: smeared with excrement and pitch. In an attempt to restore order, the senior merchant Pelsaert began a hunt for the culprits, but the men protected one another and the truth remained hidden under a cloak of silence. What is more, Pelsaert fell ill, and had to relinquish his leadership to Captain Jacobsz and the junior merchant Cornelisz. It thus seemed as though the ship had fallen into their hands of its own accord, but when it became clear that Pelsaert was not going to succumb to his illness, the mutineers resolved to take over the ship by force of arms.

On 4 June 1629, shortly before the plan to mutiny was put into action, the Batavia foundered on a rocky island sixty kilometres off the coast of Australia. The ship was lost, but most of those on board managed to reach the safety of a couple of uninhabited islands. Pelsaert went almost instantly in a sloop to fetch help and drinking water. He took more than 40 people with him, including the untrustworthy Captain Jacobsz and Zwaantje. They stayed away much longer than expected, having sailed on to Java after their failure to find drinking water nearby. They managed to reach the town of Batavia, where the governor-general, Jan Pietersz Coen, immediately had a ship made ready to fetch the shipwrecked passengers and crew.

Meanwhile the mutineers who had been left behind found themselves in a perilous position. They knew that plotting mutiny was punishable by death. Moreover, food and drinking water were extremely scarce. Jeronimus Cornelisz – according to the ship’s hierarchy, the highest in rank since the departure of Pelsaert and Adriaan Jacobsz – came up with a drastic solution. He gathered together a group of confidants – among them the original mutineers – and ordered them to kill the other men, women and children. A bloody massacre ensued, in which ninety-six men, twelve women and seven children lost their lives. The mutineers spared seven women, five of whom were intended for ‘general use’ by the entire group of mutineers. Lucretia Jans and another young woman (the daughter of a clergyman) were given preferential treatment: they were required to share their bed with only one man. Jeronimus Cornelisz chose Lucretia to keep him company in his tent. He admitted later on to raping her numerous times.

When Pelsaert returned from Batavia six weeks later to fish up the sunken cargo and save the survivors of the shipwreck, one of the soldiers who had managed to escape the massacre warned him of what he would find. Pelsaert did everything he could to restore order: witnesses were heard and mutineers arrested, interrogated, tortured and condemned. The worst of them, including Jeronimus Cornelisz, were hanged on the spot. Taking along the remaining survivors, Pelsaert set sail for Batavia, where he arrived in December. The mutineers were imprisoned and severely punished.

A dubious reputation

The Council of Justice of Batavia took statements from witnesses and came to the conclusion that Lucretia Jans was an accessory to the crimes, considering the great number of statements that incriminated her. But Jeronimus Cornelisz had always isolated her from the others, and there had been no contact between Lucretia and the other victimised women. Furthermore, she had been in the privileged position of serving only one man, which had sparked jealousy among the other women. She was accused of ‘provocation, encouraging evil acts and murdering the survivors ... some of whom lost their lives owing to her backhandedness’. When she refused to confess to any wrongdoing, the public prosecutor asked for permission to torture her. It is not known whether Lucretia actually was tortured, but it is certain that she continued to profess her innocence, and was released soon afterwards.

Meanwhile Boudewijn van der Mijlen, the husband Lucretia Jans had set out to meet in Batavia, had died the previous year. Little is known about Lucretia’s life in Batavia, though it is recorded that in October 1630 she married the sergeant Jacob Cornelisz Cuick. It was a marriage beneath her station, but as a woman alone, a stranger in the community, and one whose reputation was severely damaged, she probably had little choice. Around 1635 she returned with her new husband to the Netherlands; nothing is known about the last years of her life.

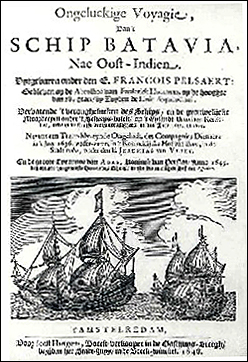

More than ten years later, in 1647, the catastrophic voyage of the Batavia became a much-discussed subject once again, owing to the publication of the book Ongeluckige voyagie van ’t schip Batavia (Unfortunate voyage of the ship Batavia), an account of the disaster based on official VOC documents. The book became popular overnight. At about this time the directors of the VOC decided to limit the number of female passengers sailing on company ships, because they disrupted relations on board merely by being there. They referred to the voyage of the Batavia as a prime example of a catastrophe caused by the presence of women.

Archives

The main archival sources on the Batavia shipwreck and its consequences have been published in Roeper, De schipbreuk van de Batavia. This publication contains the complete texts of the interrogations and confessions, fragments of the ship's journals, letters from the persons involved and lists of goods salvaged, etc..

Bibliography

- H. Drake-Brockman, Voyage to disaster. The Batavia mutiny (Sydney/London 1963).

- V.D. Roeper, De schipbreuk van de Batavia, 1629 (Zutphen 1993).

- Vibeke Roeper, ‘Schipbreuk, moord en muiterij. De reis van de Batavia in 1628-1629’, in: Robert Parthesius, Vibeke Roeper and Lodewijk Wagenaar ed., De Batavia te water (Amsterdam 1996).

- Mike Dash, Batavia’s graveyard. The true story of the mad heretic who led history’s bloodiest mutiny (London 2002).

Illustration

Title page of Ongeluckige Voyagie…(publ. 1648).

Author: Vibeke Roeperlast updated: 13/01/2014